June 1942: German Spies Land on American Beaches

- amylandis1

- Jun 30, 2023

- 6 min read

In early June 1942, German U-boats pulled up to shore and unloaded spies onto beaches in Florida and New York. In this bold attempt at foreign sabotage, Germany hoped to wreak havoc on American soil and weaken its enemy’s resolve through terror. This little known chapter in American history led to death for six men.

Operation Pastorius

Six months after Pearl Harbor, the United States was a newcomer to the world war, and had just scored a decisive victory at the Battle of Midway. Germany, hoping to dampen morale and slow the massive war machine of American factories, launched a top secret sabotage mission. Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of the Abwehr military intelligence agency, oversaw the operation. He had planned previous sabotage attempts in the first world war, including the destruction of a huge stockpile of munitions in New York Harbor in 1916. Four people died in that attack.

The Abwehr cleverly named the plan after Francis Pastorius, organizer of the first major German-American settlement in the 1600s. Operation Pastorius’s targets were high profile: hydroelectric plants at Niagara Falls; factories in Illinois, Tennessee and New York; water treatment facilities; and crucial railroad bridges and intersections, including Newark’s Penn Station. The goal was to disrupt production and interfere with commerce and transportation, as well as begin a wave of terror across the country.

Recruiting Spies

Abwehr operatives recruited Germans with good English skills who had spent a considerable amount of time in the United States. The selected group of men underwent three weeks of intense training in hand-to-hand combat, invisible ink, and explosives. Only eight made the cut after a mock mission. The new spies received extensive fake identities, including birth certificates and social security cards. They read American magazines and newspapers to brush up on current events and culture. Supposedly, they learned the words to the Star-Spangled Banner and Oh Susanna.

The key criterion for their selection appears to be familiarity with the United States, and some had American citizenship or passports. It soon became clear that perhaps they should have vetted the spies more carefully, as problems occurred before they even left Europe. One recruit, George Dasch, left a stack of top-secret documents on a train. Another got drunk and announced that he was a secret agent in a Paris bar. Regardless of the warning signs, Germany loaded the eight men onto two U-boats to cross the Atlantic in late May.

Things Go South with the Northern Group

Immediately, the mission got off on the wrong foot. The northern U-boat lodged on a sandbank less that 700 feet from the Long Island shore, leaving it in plain sight off the coast as dawn approached. The captain revved the engines and finally broke free. Four spies went ashore on June 13th in a dinghy with watertight boxes containing explosives and detonators. They landed on the beach near Amagansett in the Hamptons, less than a hundred miles from New York City. The men arrived in German Navy uniforms to ensure their treatment as prisoners of war if captured.

Waterlogged from their ocean trek, the men were changing into civilian clothes when confronted by an unarmed Coast Guardsman. They offered him a quick bribe to forget he’d seen them, which he pretended to accept before promptly reporting their location to his superiors. The group made it to a railroad station and headed to New York City before an armed patrol arrived to search the area. The patrol confiscated hastily buried equipment, and an extensive FBI manhunt began.

Meanwhile, in Florida, the southern group of spies landed uneventfully at Ponte Vedra Beach, near Jacksonville. They got on a train to Cincinnati, where they split into two groups and two of the four men continued on to Chicago. Their undercover skills were also proving to be weak, as one boasted about the mission to an old friend and another visited his father in Chicago.

Large Chinks in the Armor

Dasch, his frail allegiance to Germany weakened by their near capture, had second thoughts. He told a fellow spy named Ernest Burger he planned to turn himself in. Burger, whose allegiance was even more frail, agreed to defect with him, knowing Dasch was going to give them all up. Dasch called the FBI office in New York City, stating he had just arrived from Germany and would call back when he arrived in Washington, D.C. the next week. Ironically, he used the name “Pastorius.” Five days later, he called the FBI office in DC, using the “Pastorius” name again, and they immediately connected him. He furnished his location, and the FBI took him into custody with a suitcase full of American cash.

Under interrogation, Dasch quickly gave up the identities of all the other saboteurs and their locations. Within a week, all eight spies were in custody after less than two weeks in the States.

A Kangaroo Court?

Right off the bat, secrecy about the matter was a priority. The American government didn’t want the public to know how easy it was for two German submarines to drop off spies on beaches without being detected. J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the FBI, was taking credit for the successful dragnet, and wasn’t eager to share how Dasch turned himself in and sang like a canary. There was also concern that in a public trial in civilian court, the charges wouldn’t stick, since none of the spies committed any acts of sabotage. President Roosevelt wanted the death penalty. There was only one solution to ensure a verdict and maintain secrecy: a military commission.

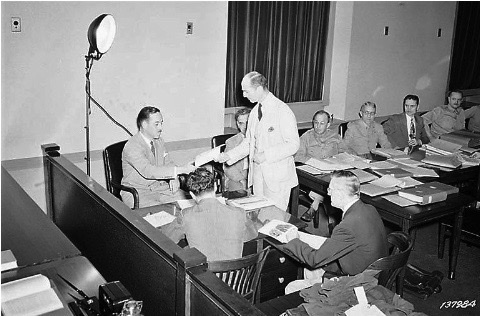

Although defense counsel argued to the Supreme Court that the commission was unlawful, formal proceedings began in early July. The lead prosecutor was Frances Biddle, who later served as a chief judge at the post-war Nuremberg Trials. He presented evidence obtained from buried boxes on the beaches, which included bombs resembling coal, safety fuses, detonator fuses and blocks of TNT.

The FBI had also confiscated a large amount of cash recovered by the FBI, which amounted to millions in current day dollars. The money was unused except $612 for clothing, meals, lodging, travel, and the $260 bribe on the Long Island beach.

The two defected betrayers, Dasch and Burger, both testified they never intended to commit sabotage. Dasch claimed he always intended to defect upon arrival. Burger was a former Nazi party member who took part in the Beer Hall Putsch, but later soured on them and turned critical. He spent seventeen months in a concentration camp in Germany for writing a paper critical of the Gestapo after serving as an aide-de-camp to Ernst Röhm. His inclusion in the group is certainly questionable, as he had an ax to grind.

The other defendants gave detailed confessions, all agreeing they committed no acts of sabotage. They testified they took part in the mission under duress to spare family and friends from harm. Two testified they planned to commit sabotage, but changed their minds when they arrived.

The prosecution argued that bringing explosives into the country violated the laws of war. They further argued that the commission should punish all attempted sabotage to send a message to America’s enemies. The closing argument of the defense was: “They did not hurt anybody. They did not blow up anything.”

The military commission found all eight men guilty and sentenced them to death.

Two Lives Spared

J. Edgar Hoover appealed to Roosevelt to spare the lives of George Dasch and Ernst Burger to encourage future saboteurs to turn themselves in. Roosevelt agreed to Hoover's request for leniency. Dasch received a 30-year-sentence, and Burger got life in prison.

The United States executed the remaining six men in the electric chair on August 8, 1942, less than a month after their ill-fated arrival.

The Aftermath

After the war, in 1948, President Truman granted clemency to Dasch and Burger and deported them to the American occupation zone in Germany. Germans did not welcome the men they regarded as traitors, and they never received the pardons Hoover had promised them for their cooperation.

In 1959, Dasch wrote a book titled “Operation Pastorius: Eight Nazi Spies Against America.” He claimed to be affiliated with the anti-Nazi underground when recruited, and that he never planned to carry out the mission. The book did little to clear his name in either country. He died at age 89 in 1992 in Ludwigshafen, Germany.

Echoes of the hasty military tribunal rippled into the future. Three of the judges on the panel later regretted their verdict. After the 9/11 attacks, lawyers cited the commission as a precedent for the military tribunals at Guantánamo Bay.

It begs the question: Is all fair in love and war? You be the judge.

This is an amazing piece of history! Thanks for telling a story so few people know. Definitely makes you think about the invisible actions we are completely unaware of.